Article Info

Year: 2025

Month: July

Issue: 3

Pages: 5-7

Dengue is a prevalent infectious disease that is rapidly rising as a global health threat. It is caused by one of the four serotypes of the dengue virus and is transmitted to humans through the bite of female Aedes mosquitoes. The disease can vary from mild fever to more severe conditions, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome (1). Worldwide, The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that dengue is currently prevalent in more than 100 nations. Up to 3.6 billion people, or 40% of the global population, live in areas where dengue is endemic (2). According to estimates, the dengue virus infects 400 million people annually, causes illness in 100 million of them, and is responsible for 21,000 deaths(3). Regionally, outbreaks have also occurred in some cities of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with efforts aimed at containing these outbreaks(4).There are limited studies that assess the sources and risk factors associated with the dengue fever outbreak in Oman.

It is essential to identify the sources and risk factors associated with the dengue fever outbreak in North Batinah Governorate (Oman) in 2023. This will aid in the development of policies and strategies to control the outbreak and offer recommendations to policymakers to prevent future community outbreaks.

We conducted a case–control study with 194 laboratory‑confirmed dengue fever (cases) and 194 laboratory‑negative dengue fever (controls). The main objective of our study is to identify potential risk factors associated with the outbreak.

Our study showed that, among the cases, 123 (63.40%) were male and 71 (36.60%) were female. The age distribution of the cases was as follows: 98 cases (50.50%) were aged 30-59 years; 50 cases (25.80%) were 60 years or older; 38 cases (19.60%) were aged 15-29 years; and 8 cases (4.10%) were aged 1-14 years. Regarding clinical presentation, all 194 cases (100%) had documented fever. Additionally, 107 cases (55.20%) had headaches, 95 cases (49.00%) had myalgia, 78 cases (40.20%) had joint pain, 76 cases (39.20%) had retro-orbital pain, 33 cases (17.00%) had nausea, 21 cases (10.80%) had abdominal pain, 10 cases (5.20%) had a skin rash, 1 case (0.50%) had impaired consciousness, and 1 case (0.50%) had gastrointestinal bleeding. The study also showed that 156 cases (80.40%) were Omani, and 38 cases (19.60%) were non-Omani. Among the non-Omani cases, 17 (44.70%) were Indian, 14 (36.80%) were Bangladeshi, 2 (5.30%) were Pakistani, and 1 case (2.60%) each came from China, Myanmar, Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt. Based on travel history, 166 patients (85.60%) had no travel history, while 28 patients (14.40%) had a history of travel. Regarding the severity of cases, 123 patients (63.40%) were admitted to the hospital, and 71 patients (36.60%) were followed up in the outpatient department. In terms of outcomes, 193 patients (99.50%) recovered, while 1 patient (0.50%) passed away. The calculated case fatality rate (CFR) was 0.50%.

Statistical analysis showed that wilayat and travel history were independent factors associated with dengue fever; however, gender and age did not show a significant association with the disease (Table 1).

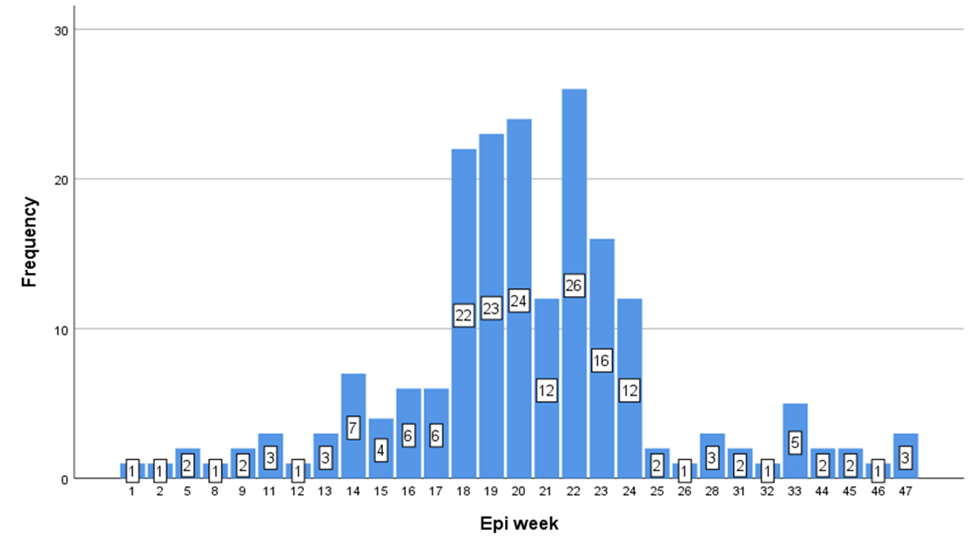

This is the third local transmission outbreak of dengue fever in the governorate, and because the vector was active and present in sufficient density, transmission was sustained within the governorate (Figure 1).

Most of the cases were adult males aged 30–59 years, which was similarly observed in outbreak investigations in India 2021(5). The reason for this may be that most males of this age spend much of their time outside the home—whether at work, shopping, or attending to other needs—resulting in greater exposure and a higher risk of dengue fever infection.

Our study showed that traveling to endemic areas increases the risk of infection, as reported in another study(6). Fever, headache, and myalgia were the most common presenting clinical manifestations in patients, as reported in this study, which was also observed in another study(7). Our study also showed that Sohar recorded the highest number of dengue cases in the governorate during this outbreak, likely linked to its large expatriate population, some of whom had recently traveled to endemic areas like India(5), which may have initiated local transmission. Additionally, Sohar has high-risk areas such as Al Tareef, Humbar, and Waqaiba, which have a high number of expatriates and farms. These factors contribute to a high density of vectors and breeding sites, as these farms have stagnant water, a key factor in the spread of dengue infection, as reported in another study(7). In our study, most of the cases were Omani, which can likely be explained by local transmission. The source was most likely an expatriate who introduced the disease to Omanis in the presence of a high density of vectors.

Dengue fever is a major public health issue in Oman. Our study suggests several recommendations to contain the dengue fever outbreak, including conducting entomological surveys around the index house based on a defined protocol; implementing early notification and intensive community‑wide vector control, which has proven effective at preventing further spread; identifying high‑risk populations and environmental factors for targeted interventions; ensuring that there are no infection sources, such as open water tanks, in areas with cases, and verifying that windows are fitted with screens to reduce infections; engaging community leaders and stakeholders through health committees to promote public awareness; organizing awareness lectures for health staff at various locations; conducting community education sessions and producing educational materials; and ensuring continuous efforts from various government sectors, including the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Municipalities, to contain the outbreak.

Table 1: Multivariate analysis results for different factors and dengue fever among the study sample.

|

Factors (n 388) |

OR | Lower limit of 95% CI of OR | Upper limit of 95% CI of OR | P value |

| Gender (reference group: Male) | 0.053 | |||

| Female | 1.568 | .993 | 2.476 | |

| Age (reference group: ≤ 14 year | 0.143 | |||

| 15 - 29 | .953 | .327 | 2.774 | 0.929 |

| 30 - 59 | 1.552 | .558 | 4.317 | 0.400 |

| ≥ 60 | 1.904 | .645 | 5.621 | 0.244 |

| Wilayat (reference group: Shinas) | < 0.001* | |||

| Sohar | 5.400 | 2.169 | 13.444 | 0.000 |

| Khaboura | 1.223 | .289 | 5.166 | 0.784 |

| Suwaiq | 1.743 | .559 | 5.433 | 0.338 |

| Liwa | 4.032 | 1.290 | 12.602 | 0.017 |

| Saham | 1.369 | .398 | 4.703 | 0.618 |

| Travel history (reference group: No) | 0.002* | |||

| Yes | 3.526 | 1.604 | 7.750 | |

Figure 1: The quarterly distribution of confirmed dengue infections in Saudi Arabia for 2023 and 2024

References

1. Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue Fever: Causes, Complications, and Vaccine Strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016(3).

2. Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature [Internet]. 2013;496(7446):504–7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12060

3. Sridhar S, Luedtke A, Langevin E, Zhu M, Bonaparte M, Machabert T, et al. Effect of Dengue Serostatus on Dengue Vaccine Safety and Efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):327–40.

4. Melebari S, Bakri R, Hafiz A, Qabbani F, Khogeer A, Alharthi I, et al. The epidemiology and incidence of dengue in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, during 2017-2019. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(11):1173–9.

5. Singh N, Singh AK, Kumar A. Dengue outbreak update in India: 2022. Indian J Public Health. 2023;67(1):181–3.

6. Liu W, Hu W, Dong Z, You X. Travel-related infection in Guangzhou, China,2009-2019. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;43:102106.

7. Mehmood A, Khalid Khan F, Chaudhry A, Hussain Z, Laghari MA, Shah I, et al. Risk Factors Associated with a Dengue Fever Outbreak in Islamabad, Pakistan: Case-Control Study. JMIR public Heal Surveill. 2021 Dec;7(12):e27266.

تفشي حمى الضنك في محافظة شمال الباطنة (عمان)، من يناير ٢٠٢٣ إلى ديسمبر ٢٠٢٣

يُعد مرض حمى الضنك من الأمراض المعدية الشائعة ويمثل تهديدًا صحيًا عالميًا، إذ ينتشر حاليًا في أكثر من ١٠٠ دولة. ووفقًا لمنظمة الصحة العالمية، فإن ٤٠٪ من سكان العالم يعيشون في مناطق ينتشر فيها حمى الضنك. إقليميًا في السعودية، تمّ رصد عدة تفشّيات لحُمّى الضنك في مدن مختلفة، حيث أدى ذلك إلى جهود متكاملة للحدّ من انتشار المرض. هناك دراسات محدودة تقيم عوامل الخطر المرتبطة بتفشي حمى الضنك في سلطنة عمان.

أجرينا دراسة من نوع "دراسة الحالات والشواهد" شملت ١٩٤ حالة مؤكدة مخبريًا بالإصابة بحُمّى الضنك، و١٩٤ شاهدًا سلبي مخبريًا (أي لم يُصَبوا بالمرض). كان الهدف الأساسي من دراستنا هو تحديد العوامل المحتملة المرتبطة بتفشّي المرض.

أظهرت هذه الدراسة أن الذكور بلغ عددهم ١٢٣ (٦٣٫٤٠٪)، وكان أكثر المصابين ممن تتراوح أعمارهم بين ٣٠ و٥٩ عامًا، بعدد بلغ ٩٨ حالة (٥٠٫٥٠٪). أما بالنسبة للأعراض، فقد كانت الحُمّى أكثرها شيوعًا وظهرت في ١٩٤ حالة (١٠٠٪)، تلتها الصداع في ١٠٧ حالات (٥٥٫٢٠٪). وأظهرت الدراسة أن ١٥٦ حالة (٨٠٫٤٠٪) كانت من المواطنين العُمانيين، في حين كانت ٣٨ حالة (١٩٫٦٠٪) من غير العُمانيين. كما تبيّن أن ١٦٦ حالة (٨٥٫٦٠٪) لم يكن لديها تاريخ سفر، بينما ٢٨ حالة (١٤٫٤٠٪) كان لديها تاريخ سفر. وأوضحت النتائج أن أغلب المصابين كانوا من ولاية صحار، بعدد بلغ ١٤٨ حالة (٧٦٫٣٠٪). أما نسبة الوفاة المحسوبة، فقد بلغت ٠٫٥٠٪.

اشتملت عوامل الخطر المرتبطة بتفشي حمى الضنك في هذه الدراسة على الولاية، حيث كان الأشخاص من ولاية صحار أكثر عرضة للإصابة بحمى الضنك مقارنة بغيرهم في باقي الولايات، وذلك لوجود الناقل بكثافة عالية في ولاية صحار. كما وجدت الدراسة أن وجود تاريخ سفر إلى أماكن تشهد تفشيًا لحمى الضنك يُعد من عوامل الخطر للإصابة بالمرض.

كانت معظم الحالات في هذه الدراسة من الذكور البالغين في الفئة العمرية 30–59 عامًا، وقد يُعزى السبب في ذلك إلى أن نسبة التعرض لخطر الإصابة تكون أكبر لدى هذه الفئة، نظرًا لأن غالبية وقتهم تُقضى خارج المنزل.

إن السفر إلى مناطق مستوطنة (منتشرة فيها المرض) يزيد من خطر الإصابة بحُمّى الضنك كما أوضحت الدراسة.

أظهرت الدراسة أن ولاية صحار سجلت أعلى نسبة من حالات حمى الضنك خلال هذا التفشّي، وقد يرجع السبب إلى أن هذه الولاية تضم عددًا كبيرًا من الوافدين القادمين من مناطق مستوطنة، مما أدّى إلى بدء الانتقال المحلي للحالات. كذلك، تحتوي الولاية على كثافة مزارع قد تحتوي على مياه راكدة، مما يساهم في انتشار عدوى حمى الضنك. وقد يكون مصدر العدوى من القادمين من هذه المناطق، الذين أدخلوا المرض إلى السكان المحليين، خاصةً في ظل وجود كثافة عالية من النواقل.

تشير دراستنا إلى عدة توصيات للحد من تفشي حمى الضنك، تشمل: إجراء مسوحات حشرية حول المنزل الذي به إصابة مؤكدة استنادًا إلى بروتوكول محدد؛ تنفيذ الإبلاغ المبكر ومكافحة النواقل المجتمعية على نطاق واسع؛ ضمان خلو المناطق التي ظهرت فيها الحالات من مصادر العدوى، مثل خزانات المياه المكشوفة، والتحقق من تركيب شبابيك على النوافذ لتقليل الإصابات؛ إجراء جلسات توعية مجتمعية وإنتاج مواد تعليمية؛ وضمان الجهود المستمرة من مختلف القطاعات الحكومية، بما في ذلك وزارة الصحة ووزارة البلديات، للحد من تفشي المرض.